When Ernesto first saw the desert, he thought it looked like an ocean that had forgotten how to move.

Endless sand stretched beyond the airport windows in Riyadh, glowing under a white-hot sun. He had never been outside the Philippines before, never seen land so flat and sky so wide. Back home in Bicol, the horizon was broken by coconut trees and mountains. Here, everything felt exposed.

He tightened his grip on his small duffel bag. Inside were two sets of clothes, a framed photo of his wife Liza and their two children, and a tape measure he’d owned since his apprenticeship days. It was old and scratched, but it had built kitchens, doors, cabinets, and the tiny wooden crib where his daughter once slept.

Now he was in Saudi Arabia, hired as a carpenter for a construction company building luxury villas on the outskirts of the city.

The recruiter had promised good pay. ‘Two years,” Ernesto had told Liza before leaving. “We’ll finish the house roof. Maybe even start a sari-sari store.”

At the airport goodbye, his son Marco had clung to his leg. “Papa, bring me a robot,” the boy said.

Ernesto laughed, though his chest felt tight. “I’ll bring you something better. I’ll bring you a stronger house.”

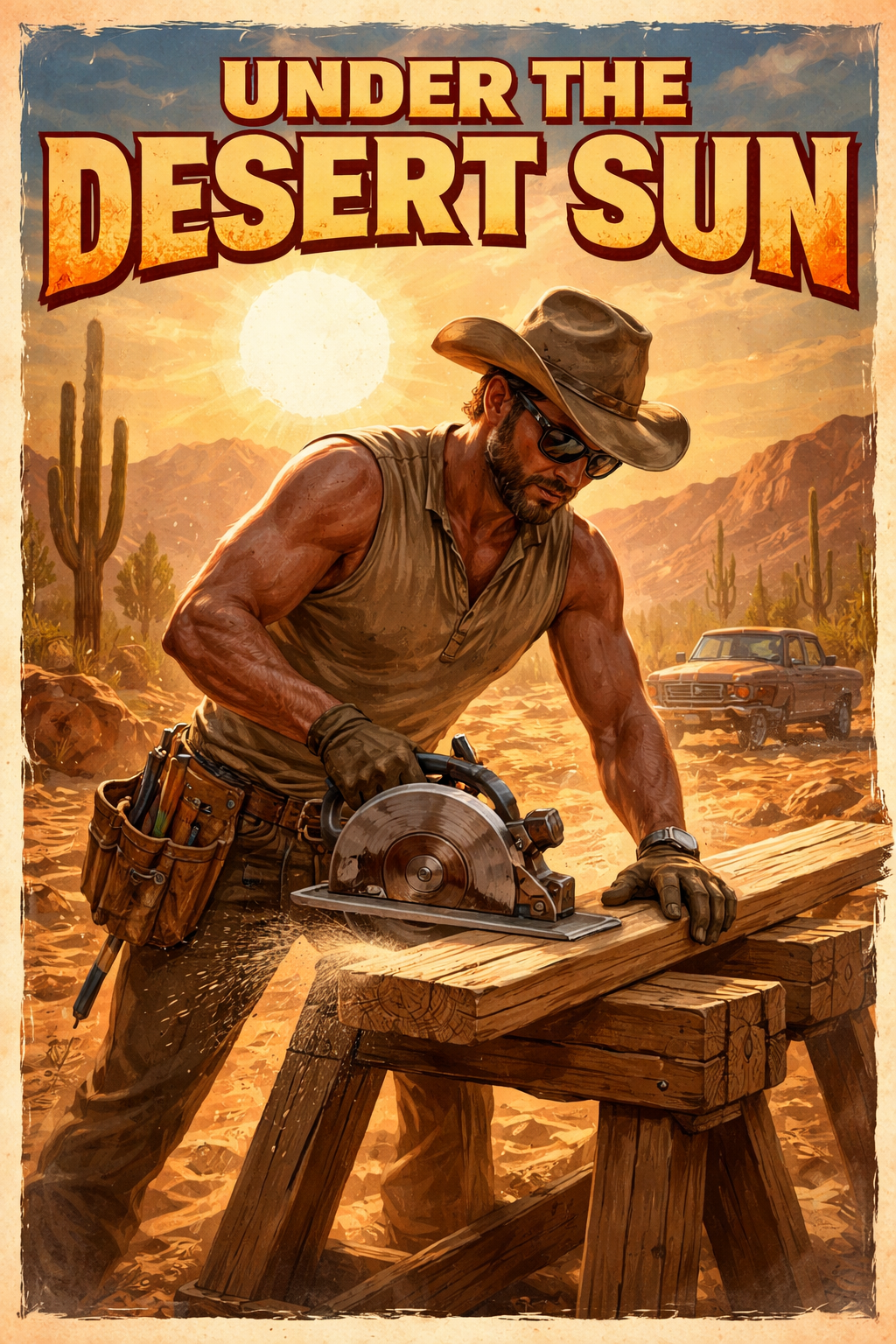

The first weeks in Saudi were a blur of heat and adjustment. The air felt different dry, almost sharp in his lungs. The sun rose fierce and high, and even in the early morning, sweat gathered under his helmet.

The worksite was massive. Concrete skeletons of villas stood in neat rows, waiting for finishing touches. Marble tiles gleamed inside. Chandeliers lay wrapped in plastic like sleeping giants. These homes were nothing like the modest concrete houses Ernesto was used to building back home.

He was assigned to interior woodwork custom cabinets, ornate doors, ceiling panels carved with geometric patterns. The designs were precise, intricate. There was no room for guessing measurements.

His supervisor, a Lebanese foreman named Karim,spoke fast English and expected perfection.

“No gap,” Karim would say, running a finger along a cabinet seam. “If I can see light, the client will see it too.”

Ernesto nodded each time. He had always taken pride in clean joints and smooth finishes. But here, the standards felt unforgiving. One mistake could mean deductions from his salary.

The worker’s accommodation was a long, low building on the edge of the city. Eight men shared his room Filipinos, Bangladeshis, Indians. At night, the room hummed with electric fans and quiet phone conversations in different languages.

Every evening, Ernesto would sit on his lower bunk and video call Liza.

“How are the kids?” He’d ask.

“Marco got highest in math,” Liza would reply proudly. “And Ana danced at school.”

He would smile at the screen, memorizing their faces pixel by pixel. When the call ended, the room felt heavier.

Sometimes he wondered if building mansions for strangers was worth missing birthdays and school programs. But then he’d remember the unpaid bills stacked on their small table back home, the roof that leaked during typhoons.

He wasn’t just building houses in Saudi. He was building security for his family.

One Friday, their day off, Ernesto walked to a nearby hardware market. The smell of sawdust drifted from one shop, familiar and comforting. He ran his fingers over stacks of polished oak and walnut.

Wood was wood, no matter the country. It carried its own story in its grain.

Back at work, a special project came in a grand double door for the main entrance of the largest villa. The design required delicate carvings inspired by traditional Islamic patterns. Karim selected Ernesto and two others for the task.

“This door must impress,” Karim said. “It is the first thing the owner sees.”

For days, Ernesto studied the design, tracing the curves with his pencil. He moved carefully, guiding the chisel with steady hands. Each tap of the mallet felt like a heartbeat.

As he carved, he thought about the narra wood doors he’d made in the Philippines simpler, but crafted with the same care. He remembered his father teaching him how to sand in long, even strokes.

“Respect the wood,” his father used to say. ‘If you rush it, it will show.”

Ernesto did not rush.

The desert sun blazed outside, but inside the workshop, he lost track of time. Patterns slowly emerged from the flat surface, shadows deepening in the grooves. The scent of freshly cut timber mixed with sweat and concentration.

When the door was finally installed, it stood tall and imposing, polished to a warm sheen. The carvings caught the light beautifully.

Karim inspected it in silence.

Ernesto felt his stomach twist.

Finally, Karim nodded. “Very good, Ernesto. Very clean work.”

It wasn’t a long speech. But it was enough.

That night, Ernesto sent extra money home.

“For what?” Liza asked over the phone.

“Start fixing the roof,” he said. “Before the rainy season.”

Months passed. The rhythm of work, prayer calls echoing from distant mosques, and shared meals of rice and canned goods became routine. He learned a few Arabic phrases just enough to greet and thank.

There were hard days. Once, he accidentally nicked an expensive panel and had to redo it without pay. Another time, news reached him that a typhoon had flooded their barangay. He felt helpless, staring at photos of muddy water inside his home.

“I should be there,” he whispered.

“But you’re helping us from there,” Liza replied firmly. “Because of you, we can repair faster.”

Her faith steadied him.

One evening, as he sanded the edge of a wardrobe door, a young Saudi boy wandered into the villa with his father. The child watched him curiously.

“You make this?” The boy asked in shy English, touching the smooth surface.

“Yes,” Ernesto said.

The boy grinned. Beautiful.”

It was such a simple word. But it warmed him more than the desert sun ever could.

He realized then that his work traveled further than remittances. It shaped spaces where families would gather, where children would grow up. Though he might never live in these grand villas, his hands would leave a mark inside them.

On his second year, his contract neared its end. He counted the months carefully. The house back home now had a solid roof. They had even painted the walls light blue, Liza’s favorite color.

“Come home soon, Papa,” Ana would say during their calls.

“I’m coming,” he promised.

On his final day at the site, Ernesto stood quietly in front of the completed villa. Sunlight reflected off the windows. The grand door he carved stood proud and flawless.

He ran his hand along the smooth wood one last time.

Two years in the desert had changed him. The heat had darkened his skin. The distance had deepened his love for home. He had learned patience, precision, endurance.

At the airport, waiting for his flight back to the Philippines, he opened his duffel bag. Inside was a small wooden toy robot he had carved from leftover scrap carefully sanded, joints moving just enough to delight a child.

He smiled.

He had built cabinets, doors, and ceilings under the desert sun. But the most important thing he built was waiting for him across the sea a stronger home, held together not just by nails and beams, but by sacrifice.

As the plane lifted off, the desert shrank below him, golden and endless.

Soon. He would see coconut trees again. Soon, he would hold his children.

And when he did, he would return not just as a carpenter from Saudi Arabia, but as a father who built dreams from wood and distance.